Teaching second grade at L. Elementary was...difficult.

As I tried to control my group of boys’ relentless misbehavior, I soon recognized that one of the problems was that they were bored.

Honestly, I was bored, too.

Educational theorist Sir Ken Robinson, in a speech on changing educational paradigms, once spoke to this particular tension in modern education, “Our children are living in the most intensely stimulating period in the history of the earth. They are being besieged with information and pulls for their attention from every platform…and we are penalizing them for getting distracted from what? Boring stuff. At school.”

Teachers are teaching in the most stimulating time in history. While there are protests in the streets, melting glaciers at both poles, apps for this and that, unfinished levels on video games, travel destinations, bestsellers and blockbusters awaiting completion, we are charged with getting children to concentrate on filling in bubbles on multiple choice tests.

Snooze.

The year the Space Shuttle Endeavor took its final flight over Los Angeles in 2012 my class and Ms. G.’s special day class were the only two classes on the schoolyard looking up into the sky watching the historic moment.

The rest of the school stayed indoors as if there was something better to engage in inside the classroom than witnessing a Space Shuttle fly over our heads. I was confounded with the decision of most of my colleagues to stay indoors rather than let the kids marvel at a spacecraft flying over us.

My students and I could sense all the fascinating things occurring in the world in real time like they were weather occuring outside our door.

Of course, we’d all get stir crazy, claustrophobic, resentful, and enraged because our education hinged on learning how to fill in the correct bubbles on multiple choice tests instead of engaging in the world.

John Holt in his book How Children Learn references professor of philosophy David Hawkins as pointing out that, “when children have no autonomy in learning everyone is likely to be bored.”

What do second graders do when they feel bored and powerless?

They start making origami. At least that’s what my class did.

A fervent origami fever swept through Room 29 like rampaging lice. The Japanese paper-folding art form was not part of our standards-based curriculum or even a favorite subject of mine, but my class of busy-fingered kids suddenly, one day, self-initiated a paper-folding craze.

In fact, they depleted the school library’s entire collection of five origami books to the point that inevitably someone would end up in tears on Library Day because they didn’t get their turn to check out one of the five books that were all checked out to our classroom anyway.

I would, attempting to be Solomonic, point out (loudly!), “Just borrow the books from each other once we get back to class! Sheesh!”

That didn’t seem to satisfy any of the kids, and the disappointed crying would continue.

I would then revert to my internal, dysfunctional, fed-up Latino dad mode and insist, “Just share the books! Share. You learned that in kindergarten, remember!? Stop crying! There’s no crying in second grade!”

Of course, they would ignore me and continue to cry not getting my movie reference. How do these children know about Freddy Krueger and Chucky but not A League of their Own?

Back in our classroom, as I would walk around checking work, the students would constantly, and secretly, be folding paper under their desks into hearts or three-dimensional boxes instead of doing their work.

Reams of my copy paper stored in my supply closet started disappearing sheet by sheet.

The magic of folding creations had the girls and boys absolutely entranced and sidetracked. They started behaving like they were part of a paper-folding cult who had to perform origami everyday in order to save the world.

It got to be too much.

The origami had become a disruption.

I started confiscating armfuls of creatively-folded forms in frustration and annoyance. Origami became a crime in my classroom.

But the repossessions were all to no avail. Origami continued to proliferate.

The folding, led by a cadre of talented Cambodian and Latina girls, initially started out as paper roses and cootie catchers, a paper toy folded into four pyramidal shapes.

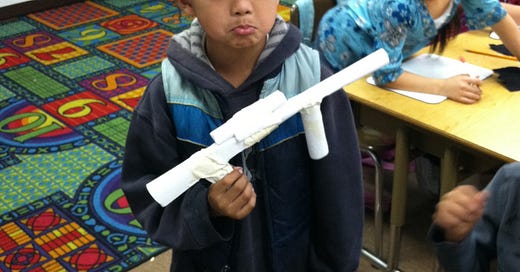

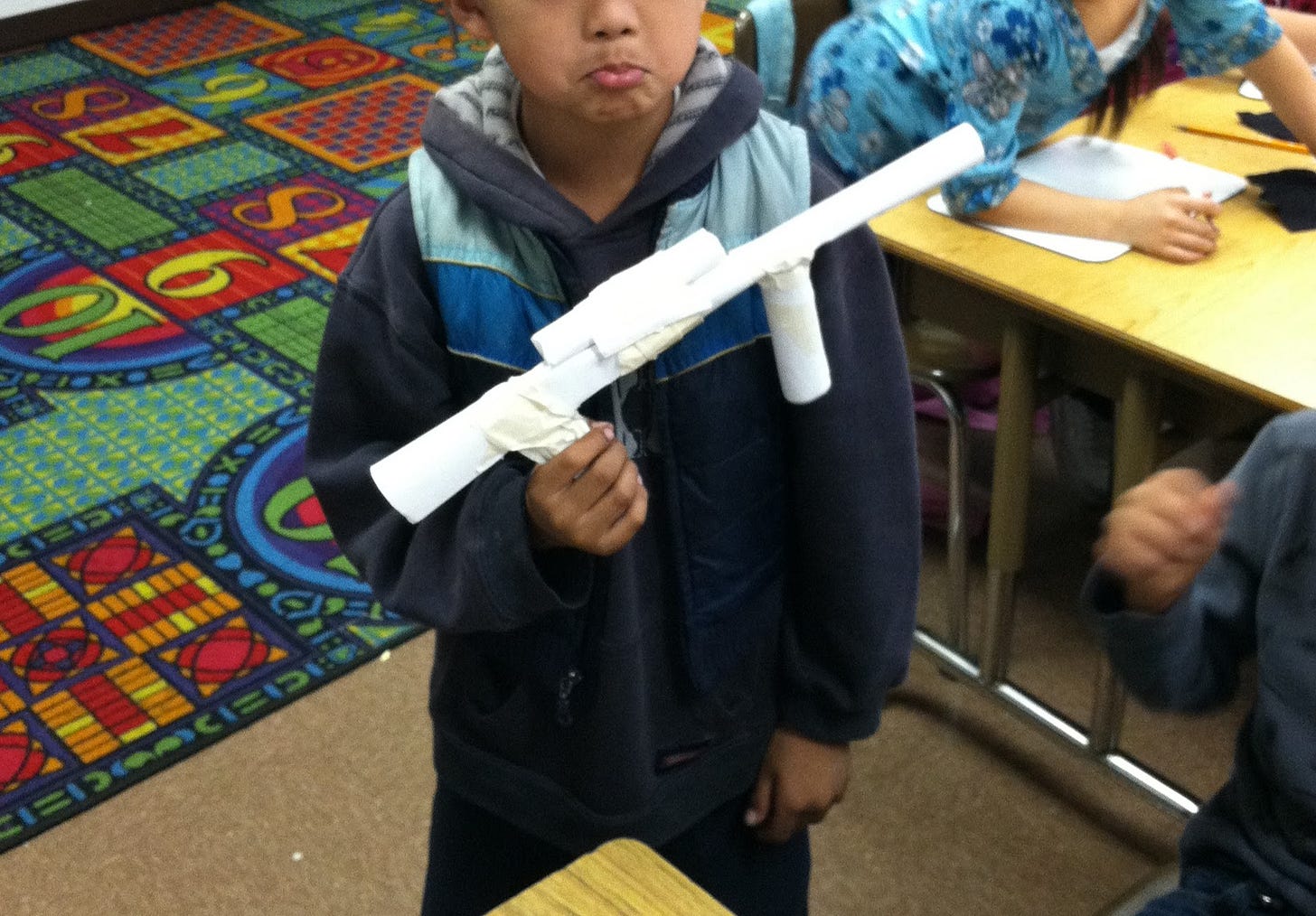

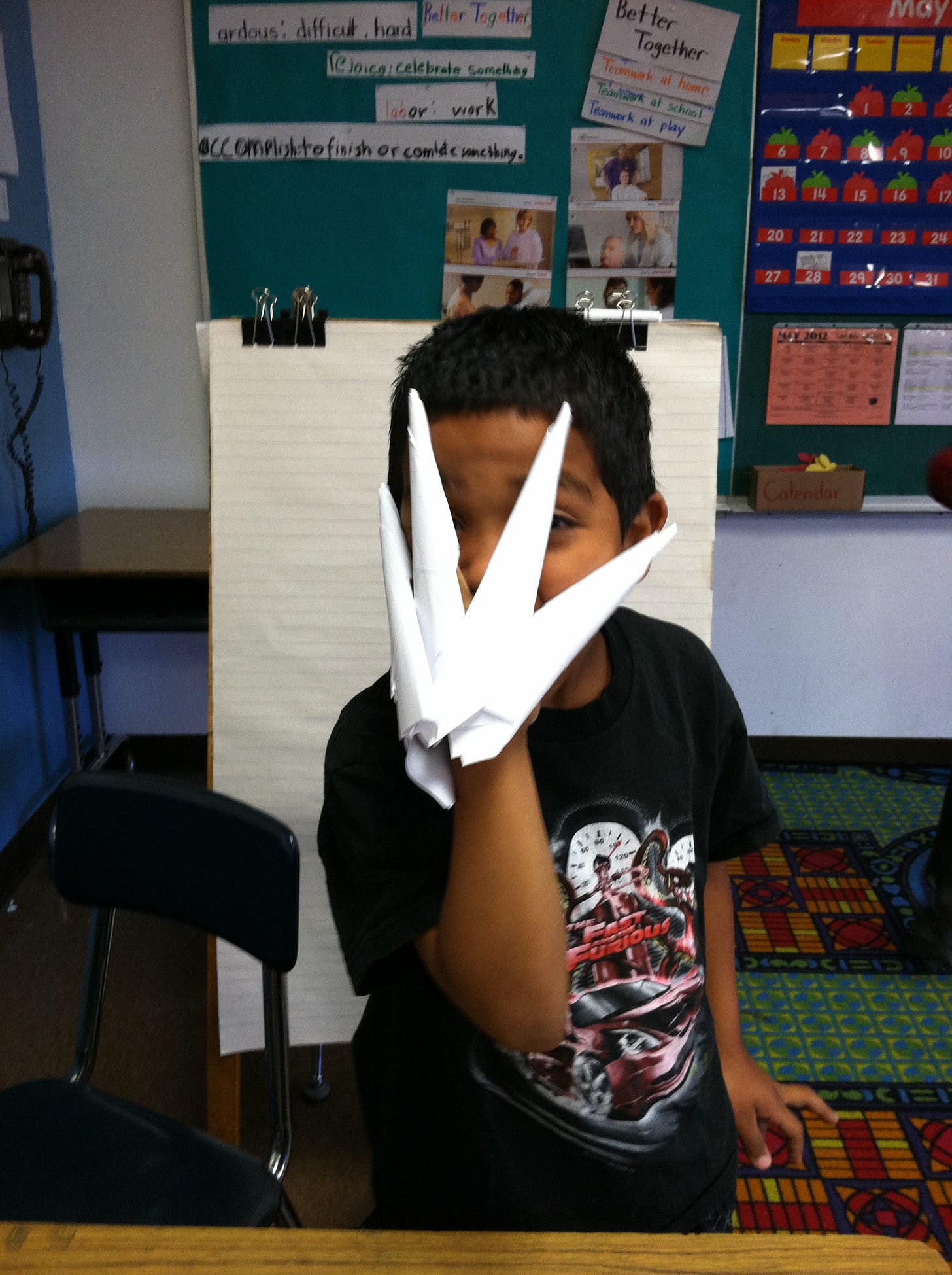

But then, as the Japanese artform crossed the gender line, it advanced (or devolved?) into an arsenal of spinners, ninja stars, AK47s, rifles, pistols, and, of course, the Freddy Krueger glove of knives Danny was making when he announced he was King of the Bad Boys.

Room 29 became an origami gun show.

The girls’ crafting progressed into making baskets, mini-cities, and paper iPods, but the boys began constructing full-on weaponry equipped with paper silencers, riflescopes, and tripod gun rests. I eased up on my confiscations because too many students were making items simultaneously and the creations kind of became…badass.

I know teachers are not supposed to encourage gun culture. But honestly, I was impressed.

I’ve never been overly perturbed by boys’ (it really is a boy thing) affinity for bombs and semi-automatic weapons despite the multiple massacres that have erupted nationwide.

I was a boy once, too, and I adored shooting water guns, decapitating dandelions, and playing earthquake. The draw of play-destruction was always present in my boyhood.

But I also understand that what boys love isn’t guns per se. What they really love is feeling powerful, even if they don’t know that that is the feeling they pursue through their gun play.

I had also been recently maligned for my own form of gunplay.

The book of short stories I had self-published the summer before I arrived to L. Elementary, besides having tales of rimjobs and mustache bumps, pictured a gun on the front cover, a water gun, if you looked closely enough.

A gun features in one of the stories, also.

Some of my A. Elementary coworkers, after reading the book, took the plot of one of the stories as a foreshadowing that I was about to go postal on them—or at least that was one of the complaints they played up to the district during my secret threat assessment and as grounds for my removal.

I had never made a violent threat toward any of them but having called them names and alluded to their ineffectiveness as educators, having flashed my anger at them so brazenly, coupled with writing a book featuring a (water)gun on the cover they immediately jumped on my art as evidence of a reasonable fear in their attempt to get me fired.

Making brown men into violent dangers is not too difficult of a task. By default, people are afraid of us.

I ultimately decided I wasn’t going to overreact to the kids’ paper guns in the same way.

The AK-47 Jack and David and Danny and Devon had fashioned out of copy paper wasn’t ever confiscated by me.

In fact, I praised their crafting skills and offered to take a photo of their artful construction.

And, ultimately, the origami craze of Room 29 died out.