Teaching is Crying: America the Beautiful Edition

Part 5 (and last installment) of the Chillona Chronicles

Often, when I need to make myself cry in order to break the seal of pent-up, burnt-out teacher-numbness, I search YouTube for clips of deaf people getting their cochlear implants turned on. Witnessing a baby hear their mother’s voice for the first time or a grown woman finally being able to listen to her partner speak is an unfailing tearjerker for me. I use TikTok and Reels to laugh, then I use YouTube to cry.

After decades of teaching, it actually takes a lot for me to cry (although when Beyonce performed “Break My Soul” at her recent Renaissance tour date in LA, let’s just say, I had a moment). An educator can easily become inured to the multitude of tragedies that befall both our students and our colleagues over the course of a school year. Schools are communities made of the very young and the very old and the very vulnerable. They are bound to suffer misfortunes. Working at a large, inner-city public school it would not be unusual to have a teacher get a cancer diagnosis the same week you are filling out multiple child abuse reports. This is not an occupation for the faint of heart.

But on top of all the quotidian sufferings that is everyday life, the last decade has seen a particular, peculiar increase in the political and ideological malice directed at children, teachers, and public schools.

People be hatin’. And the hatin’ be hard.

Federal Rapture

On August 7, 2019, Immigration and Customs Enforcement performed raids on seven chicken processing plants in central Mississippi. In fact, it was the largest single-state immigration raid in U.S. history. Six hundred eighty undocumented immigrants were arrested. It was a federally enforced Rapture-like event where loved ones were suddenly disappeared (even if, temporarily) from their own lives. The abandoned cars of detained employees filled the poultry plants’ parking lots that night.

August 7th was also the first day of school in many of those Mississippian towns and cities.

Schoolchildren, whose parents had been detained, were left weeping for unarrived mamis and papis. The biggest existential fear for small children on the first day of class is that they will be abandoned, not picked up. It looks like ICE took full advantage of such a primal fear and used it as psychological leverage.

As pointed out by Adam Serwer in an October 2018 article in The Atlantic, the cruelty of the forty-fifth president’s federal administration (and his predecessors and successors, as well) was the actual point of these ruthless actions and policies. Serwer delineated a history of purposeful malice in this country connecting the grinning white folks photographed at public lynchings of Black people to the current era of purposeful separation of migrant families. Cruelty has been the way white Americans build community with each other, Serwer insisted. The former president’s supporters are bound together by their delight in the sufferings of immigrants, Muslims, Black people, Asians, and people of the LGBTQ community.

The crying schoolchildren were not a side effect or even collateral damage of such policy actions. They were the entire point. The whole project was (and is) to get Latino immigrants to be as miserable as possible so that they leave the country. (Although as Latino USA’s excellent reporting on the situation in Mississippi has pointed out, many of these workers returned to the towns they lived in prior to the raids accepting the whiplash of being classified unauthorized immigrants one moment then categorized as essential workers once the pandemic hit).

In the midst of all these terrible and hurtful policy choices (on immigration, on gun control, on public health, on school curriculum, on gender issues) there are the teachers and the children just trying to make due in school.

Crying and Writing and Teaching

In July of 2015, I was in San Antonio attending the Macondo Writers’ Workshop (which I was ultimately kicked out of, but that is whole another story for another time, friends).

Author and educator Joe Jimenez was also participating. I’ve have known Mr. Jimenez for a very long time. He is a high school teacher in San Antonio as well as a superb poet and YA author. Having such a talented Latino teacher is a boon for any school system but is especially vital in places like Texas.

Mr. Jimenez and I were McNair Scholars together in the late 90s. Named after Ronald McNair, the Black astronaut who perished in the Challenger space shuttle disaster, the academic program focused on preparing underrepresented undergraduates for graduate programs.

During our McNair program Joe and I made mutual friends of a young Black and Latina student named Michele Isabel Silas. We all became fast friends.

That summer in the late 90s Michele, Joe, and I spent a lot of time together on the campuses of the Claremont colleges being ridiculous, raucous, yet also intellectually curious. Half the time we were laughing, the other half we were studying (and getting into fiery debates with the other students).

After the program ended, the three of us essentially went our separate ways while simultaneously following similar paths. We didn’t all make it to graduate school, which was the intent of the McNair program, but instead we all became educators.

However, not even two years into her career as a second grade teacher in Pasadena, California, 25-year-old Michele developed an aggressive form of bone cancer. She succumbed to the disease within a year of finding out.

Michele once visited my kindergarten class while she was undergoing chemotherapy treatment. An African head wrap stood in place of the luxuriant afro she once sported. She used a cane to help her manage a limp acquired after various leg surgeries. During her visit to my class she taught me and my students how to sing “Who Stole Cookies From the Cookie Jar?” A song I ended up singing throughout my teaching career.

Although I was there in the hospital the afternoon she passed away, I didn’t cry. That only happened when I had to verbalize to my mom that Michele had died. Saying the words out loud somehow made the circumstance more real and more upsetting to me.

In 2015, long after Michele had succumbed to cancer, Joe and I reunited at the Macondo Writers’ Workshop.

He and I were still on parallel paths as writer-educators eking out a creative professional existence during the school year while also enjoying our duty-free summers by taking the opportunity to focus on the craft of our writing.

He was in the poetry cohort; I was in the fiction writing cohort.

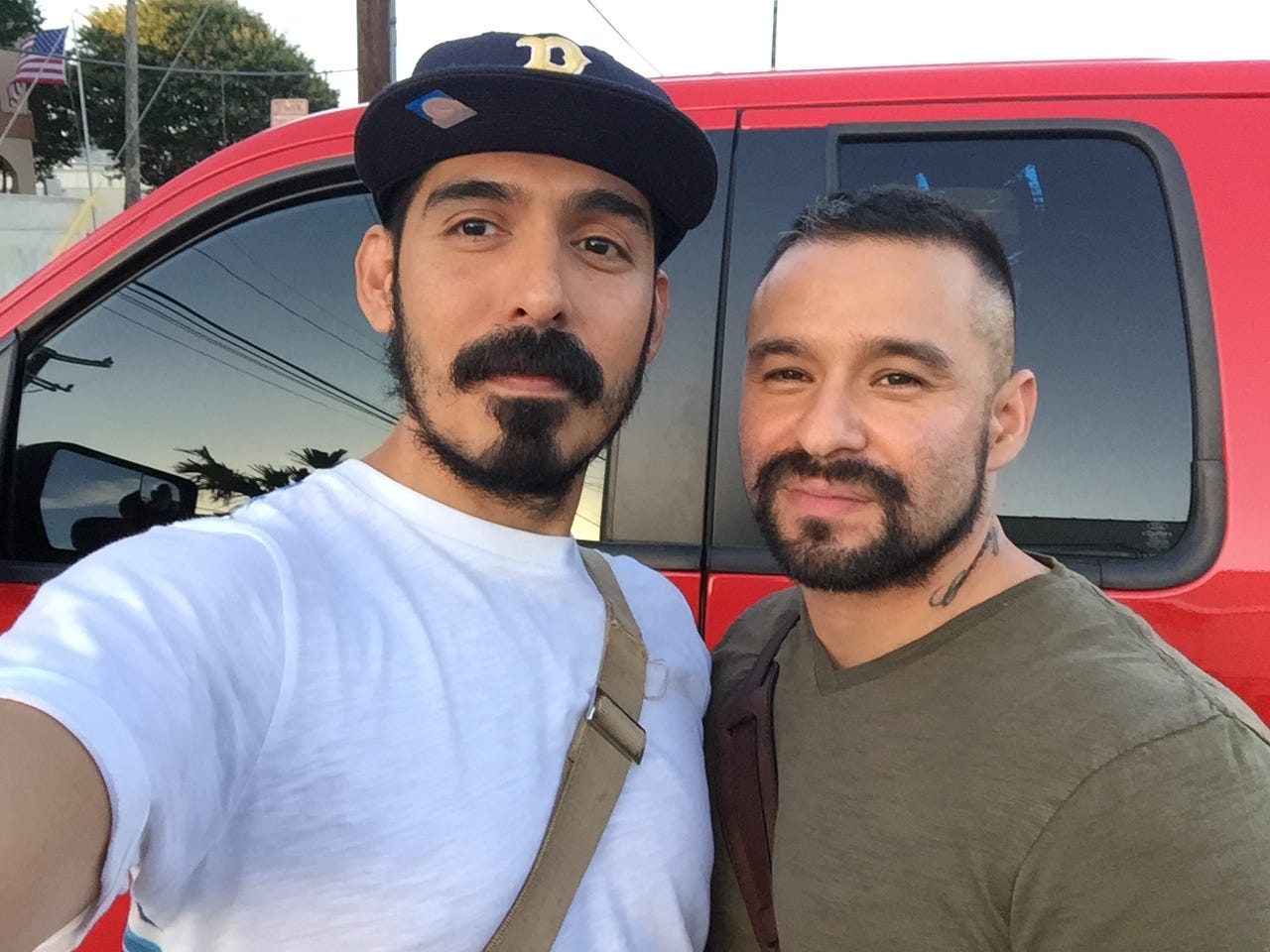

One afternoon, during that week together in Texas, after lunch and a trip to visit his home and his doggies, Mr. Jimenez and I were riding in his pickup truck (I owned a Dodge Ram 1500 at the time partially influenced by the fact that Michele had once said to me that she always wanted to drive a truck). We were returning to the Guadalupe Cultural Center located on San Antonio’s Westside where the writers’ retreat was taking place.

On this particular afternoon, Joe and I were sharing our experiences as teachers and exchanging tales about our students. I was telling him about my students and their difficult lives and how they often inspire a lot of my fiction writing.

He was telling me some of his students’ stories, relating their hardships, and the pain some of them have had to endure as they attempted to make their way through something as taken for granted by middle-class Americans as high school. He told me of his students’ poverty, their familial dysfunctions, their heartbreaks, and, sometimes, even their deaths.

As he drove and story-told, Mr. Jimenez started to silently weep.

The tears rolled down his cheeks as the whir of his truck on the road overwhelmed both of us. We were headed back to our writing workshops, finishing out our summer break, which would ultimately then return us back unto our classes, our jobs, our students, and their stories.

As he wept, I kept silent. Letting the large, heavy sigh that can sometimes be our jobs dissipate into the dry summer Texas heat.

I didn’t have to ask him why he was crying. I already knew.

We’re teachers.