It irks me when those videos of maniac-looking teachers rapping or dancing or singing with their students go viral.

Not only do the videos seem to insist much too strongly, look how cool teachers can be! but the seemingly over-industrious educators somehow turn classroom lessons into cheap performances seeking “hearts” and “likes” on TikTok or Instagram Reels.

These videos not only proliferate on social media but sometimes end up on the “good news” segment of the local news. Such famous viral sensations include the teacher who designed an individual dance routine FOR EACH of his students which he used to greet them with every single morning (how time consuming!). There are also viral videos of teachers karaoke-ing Lizzo or duetting with Adele and their class.

And then there are also really cringey videos such as the Riverside teacher who was teaching a trigonometry lesson about sine, cosine, and tan angles using a mnemonic device she made up called “soh-cah-toa.” She wore a paper feather headdress while then doing a highly offensive dance that purported to imitate Native Americans. The video is painful to watch. She turns her math class into a white one-woman powwow of cultural denigration.

Either way, well-executed or politically cringey, such performances come off as unnecessary and exhausting to me. On top of every other role educators occupy we’re now supposed to be street buskers as well?

I refuse to rap my math lessons or hip-hop my way through language arts or sing instructions about how to use grammar. My reaction to those videos is to want to become even more boring just to spite the people who expect teachers to also put on a song-and-dance on top off all the other tasks we have to do.

But…then…the other day I was reading an old note one of my teaching aides gave to me at the end of a school year and in the middle of the card she wrote, “Not to sound like a weirdo, but I liked watching you because I loved to see how you interact with the kids. I mean, how many teachers do you come across that will sing Boyz II Men to their students? ...My teachers never sang to me!”

What?!?

I absolutely have no memory of ever serenading my kids with Boyz II Men. Why would I even do that? And what song was I singing? Motownphilly? End of the Road? I’ll Make Love to You?

It was with her note that I had to reflect and then admit that when teaching I am probably unconsciously singing about a third of the time. Afterall, teaching is singing. Especially in kindergarten. The songs can range from the quick and utilitarian such as the kindergarten banger from Barney “Clean up, Clean up, Everybody, Everywhere” to whatever is hot on the Pop and R&B charts.

Pro tip: When teaching the calendar, Cherelle’s 1985 hit Saturday Love is just as useful, and even more fun to sing, to the kids than Greg and Steve’s Days of the Week.

For me the roots of this is pedagogical musicality are in 8th grade where Sister Catherine Mary would sing with us students every week, if not every day.

She taught us students a large catalog of songs that we sang at Friday and Sunday masses. Led by her, us schoolchildren belted out heartfelt renditions of Seek Ye First, Immaculate Mary, Hail Holy Queen, and On Eagle’s Wings. For a real rollicking time Sister Catherine would lead us in the up-tempo It’s Brand New Day where, as a class, we made the hallelujahs in the song reach the rafters of the church. Us eighth-graders loved singing with our teacher and each other even if we were too cool to admit it at the time.

One day Sister Catherine Mary wanted us to join her in singing We Shall Overcome, the gospel song which became an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement. However, she soon realized that her class of Chicano kids in East LA in the late 80s had no idea what song she was talking about. The tune wasn’t exactly a chart topper on the radio at the time.

By the late 80’s the zenith of the Civil Rights Movement had long passed. Our contact with the Movement’s songbook was almost nil. As students we could surely identify Martin Luther King Jr., he was an entire three-day weekend in January after all, and his resounding voice in the “I Have a Dream” speech was definitely in our intellectual ether (it had been featured on an episode of The Cosby Show). Our knowledge of the Civil Right era, however, never went deeper than such superficial exposure. None of us kids had ever heard the song because no adult had ever taken the time to explicitly sing it to us.

Sister Catherine realized that task fell to her.

So, she grabbed her guitar and got to singing. There was no record player or cd player or cassette she popped into a tape player. There wasn’t even a film she inserted into the classroom’s VCR. Her teaching was pure analog. She offered some quick contextualization as to the history of the song and then went directly into her live, impromptu performance. First, she sang it by herself— for us. An offering. Then we mimicked her. That’s how she taught us all her music.

For us, schooling was Sister Catherine Mary, unplugged.

Now despite the fact that us students were in Catholic school receiving a strict and ordered religious education, we were still East LA barrio kids. There was plenty of gritty ‘hood life being absorbed by us 12 and 13-year-olds at this time. Many of us were probably growing up too soon, clumsily being adulterated by sex and violence and poverty. I can recount 12-year-old Brandi’s bruises on her lips supposedly received by the rough kissing of her legally-adult boyfriend. There was also Andrea’s pill popping suicide attempt due to a forlorn puppy love as well as 12-year-old Eddie’s joyriding of his dad’s pickup truck which went curiously un-noticed by any parent or authority in the ‘hood.

While all this growing-up-too-fast was a-happening there were simultaneously moments when we were still just kids, innocents really, playing tetherball, re-enacting Christ’s passion in school plays, offering nosegays to the Virgin on her feast day, and singing with our nun-teacher like some outtake from The Sound of Music.

Even the ruffian boys, often more interested in LL Cool J and break-dancing, relaxed their cool a bit and gave in to the collective, prayerful joy that was Sister Catherine Mary strumming her guitar, killing us softly with her devotion.

The reverent and the holy had been something instilled in us since we were small children and, honestly, we couldn’t help but love the catchy, familiar church melodies. As curators, teachers make substantial contributions to students’ knowledge simply by singing songs and playing records for their students. This pedagogy seems quaint and old-fashion, almost rural, in its simplicity but it’s truly effective.

When teaching us We Shall Overcome Sister Catherine didn’t unfurl an entire month-long thematic unit on the Civil Rights Movement nor did she force us to read some dry tome about the historical precedents of that time. She wasn’t sledgehammering CIVIL RIGHTS! CIVIL RIGHTS! CIVIL RIGHTS! into our brains. We didn’t have to construct anything or present anything except our ready and willing singing voices. There were no Common Core standards, or any standards of any kind.

Instead, she educated us in the way that was suited best to her personality and talents. As one individual educator she couldn’t be expected to deliver the entirety of the Civil Rights Movement and its meaning in a couple of lessons. This singing was, instead, her small personal portion of a much greater whole. No one teacher can teach or deliver the completeness of “The Civil Rights Movement” but simply offer their slice of it.

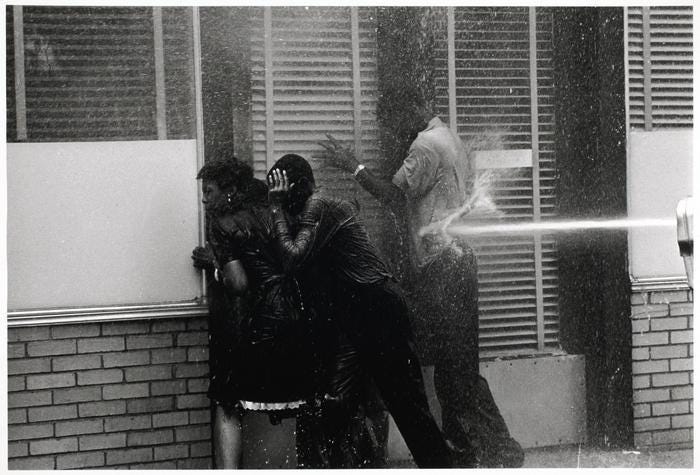

Eventually, when I later encountered that grainy, black-and-white 1960s footage of Black protesters in the South being hosed down and mauled by dogs and trying to cross bridges or sit at segregated lunch counters, I was more equipped. I understood that there was an overcoming to be had by Black people, in particular, and Brown people by extension.

I had been primed by Sister Catherine Mary and her singing to contextualize Dr. King’s speeches (and Joan Baez’s rendition of the song at the 1963 March on Washington) because I myself had sung that very same song with my classmates. It’s a song to be sung by groups like a chant or an anthem or a sing-along played during a ballgame. The song vibrates crowds, aligns hearts, hums a community. And I know that, because that’s the experience Sister Catherine created for me and my classmates.

I suspect nowadays if a general education teacher spent an afternoon singing with her class without a structured nine-point lesson plan or an obvious alignment to the state standards or under the guise of practicing for some future school performance, I suspect it would be frowned upon by administrators. What standard are you teaching by singing that song? might be a question asked of the educator. The implication being that singing isn’t standards-based unless siloed in some music theory or choral class. The expectation is that we need to cross-reference the name and number of the standards in relation to our lessons as if they are laws to be followed in a penal code.

Sometimes teachers just want to sing for singing’s sake. Sometimes that calls for an impromptu Motownphilly, other times it’s We Shall Overcome.

In my grammar school education, a teacher singing to their class was so commonplace I almost didn’t realize it was something unique until my TA mentioned it in her letter to me. I now suspect the Catholicism of my education kept the tunes coming for a longer period than what I would have received in public education unless I was enrolled in a performing arts program. My education was deeply ritualistic and ceremonial and, by default, musical.

The songs, however, did eventually peter out. High school was a lot less musical than grammar school. I soon disregarded the fact that singing is teaching. By senior year of high school, education had become about reading prodigious books and working through flashcards and filling in multiple choice exams and note-taking during long-winded lectures. Those activities, not singing, would assure my entrance into university. And they did.

Then, in the fall of 1994, my junior year of UCLA, my Political Science 10 professor surprised us undergraduates by ending our very last class-lecture before finals with a serenade.

He revealed a guitar hidden on his lecture dais and then took it up to offer us his rendition of Redemption Song by Bob Marley.

Although some students seemed uncomfortable with his performance and giggled at our professor’s less than professional voice, his singing nearly brought me to tears. I was moved. The memory of Sister Catherine Mary and how my teachers always used to sing for us students returned to me. I was 20 years old, encountering Bob Marley for the first time while also experiencing the nostalgia of having my teacher sing to me.

Besides reading Plato and Thomas Paine, the only thing I truly remember about that professor and his Political Science course is this song he rendered in a faux Jamaican patois carrying a powerful message about emancipating ourselves from mental slavery and how nobody but ourselves can free our minds.

A truer lesson if there ever was one.