Sexy Math, Naked Ladies, and Other Elementary School Tales of Danger and Tears

Part 3 of the Chillona Chronicles

The Salem Witch Trials are always just one miscommunication away for teachers.

I was teaching a first-grade math lesson on sets (collections of numbers) when Adolfo in the front row kept laughing at what I was saying.

After a few repeated bursts of giggles, I finally stopped to ask him what was so funny. The six-year-old told me he was laughing because I kept saying “sexy.”

What?! (It took me a second to figure out what he was talking about.)

When I did, I corrected him immediately, and LOUDLY. I wanted the entire class to hear, “Set C, Adolfo! I’m saying Set C, not sexy!”

I was so immediately insistent and loud because I was imagining his mom asking him what he did that day in class and him answering, “Mr. Villegas was teaching us about sexy math.” I then imagined a round of administrative investigations. Maybe even a stint in Teacher Jail.

Teachers, if they happen to catch on to such miscommunications, need to immediately and boisterously nip them in the butt…I mean…bud.

Giving Her the Run Around

My kindergartener Audrey was running around the classroom. Like most demon children, her body was facing one way while while her face was turned the other. She soon crashed into me, bounced off my leg, and fell flat onto the floor. Nothing but her pride was hurt, but she promptly stood up and immediately announced to everyone, “Mr. Villegas kicked me!”

Thank God my team partner was in the room and witnessed the collision. She immediately corrected the future Cop-Calling-Karen, “Audrey, you were running around the class, which you were not supposed to be doing, and you crashed into Mr. Villegas.”

Meanwhile my own interior dialogue was repeating, Bitch, I didn’t kick you. I stood silent, however, giving my team partner all the leeway to audibly correct the record. Then I gave little Betty Parris (one of the Salem witch trial instigators) the side-eye and stayed away from her for the rest of the day.

The Salem Witch Trials are always just one overheard child away, especially when innuendo is combined with an administrative school culture set on treating teachers as untrustworthy employees. Some administrators even pride themselves on being trigger-happy with punitive measures and investigative fishing expeditions.

Having other adults in the classroom, not only as witnesses but as laughing partners, is essential to a teacher’s personal sanity and safety.

Bobbing for Trouble

For one kindergarten Halloween celebration, I ill-advisedly decided to revive the old-fashioned game Bobbing for Apples.

I filled a large plastic tub with water and dropped in a full bag of Red Delicious. I was excited about the fun my kindergarten class was about to have with this giant container of water and it’s floating fruit. The children, not using their hands, had to dunk their heads into the depths of the tub to try to grab the apples with their teeth. Tons of fun, right?

It was a complete, utter mess.

The kindergarteners, of course, loved the insane disorder of the game. They were dunking their heads into the tub without hesitation, and sloshing them back out like happy, baby seals during an aquarium’s feeding time. The girls with long hair would jerk their wet heads out of the tubs as if they were mermaids, unbothered by the spray resulting from their soggy hair whips. The water, made gray by the washed-off Halloween makeup, spread all over the classroom as if a sewer pipe had burst. I was a little taken aback by how quickly the game devolved into soggy anarchy. I hadn’t thought the whole scenario out very well, apparently.

One little girl, who was not in costume because her family was deeply religious, was so soaked she was becoming chilled by the classroom’s air-conditioning. Her teeth chattered and she began to shiver. I instructed her to go to the restroom and remove her undershirt so we could wring it out in the sink and then lay it over a chair to air dry. She wore another button-up shirt that was also wet, but I figured let’s at least dry out the undershirt so she wouldn’t be as soaked and cold as she was. She went to the restroom and did exactly as I asked.

When it was almost time to go home, I told her to go to the restroom and put the now-dry undershirt back on. She did so.

What I didn’t notice was that she had put her undershirt back on inside out and backwards and had re-buttoned her outer shirt crookedly. Also, by this time her wet hair had dried itself into a tangled lion’s mane of a mess. She looked like she had been electrocuted. However, at the end of the school day I was too busy lining up the other kids and passing out homework and jackets to really take a close look at her.

When her mom came to the door to pick her up, the deeply religious Spanish-speaking immigrant woman’s face instantly screwed up into a suspicious, quizzical glare. She was like, “Why is my daughter’s undershirt inside out and backwards? What the hell happened to her?”

I started explaining to mom, maybe a little too excitedly, about the game we had played earlier. But I didn’t know how to say “Bobbing for Apples” in Spanish, and I was babbling on and on, stutteringly using my limited Spanish vocabulary, trying to describe what must’ve seemed like a ridiculously American scenario involving apples and biting and tubs of water.

To be honest, I must’ve sounded like a guilt-ridden person trying to come up with some ad hoc cockamamie story to explain why her child would need to take off her shirt at school in the first place. The mother looked at me in a very doubtful, McMartin-preschool type of way.

Ultimately, however, she believed what I said after her daughter stepped in and helped explain in more comprehensible Spanish why her undershirt was not in the same order as it had been when she left the house that morning.

That was the last time I ever played that stupid game.

Centerfolds

The Getty Museum in Los Angeles offers free entry, free teacher workshops, and free school buses for Title 1 schools. Their educational resources are a real boon to the city’s educators and students. By participating in their professional developments, I’ve learned how to decipher aspects of European art, and I even studied how to properly sketch a nose (you don’t draw a nose directly, you shade the area is around it).

The Getty’s teacher trainings are what professional development should be—informative, useful, and fun. In another workshop, they taught us how to identify the goddess Venus in art—she often has wavy tresses, pearls in her hair, and marine animals at her feet referencing her birth from the sea. And she is almost always depicted nude.

One year I was diligently preparing my kindergarten class for a visit to the art campus: showing them a video about the Getty, reading a book about its history, and preparing them with stories about the people-mover tram we would take up to the museum. I had the kids touch clear book tape with their grubby hands and then held the tape up to the light to show the kids how we all have unseen oils on our fingers and that’s why we can’t be touching the art.

I also warned them that we were going to be seeing a lot of naked people and some violence in the paintings and sculptures, and I didn’t want them to overreact or be too silly as we walked through the galleries. My pedagogical intention was to teach them how to comport themselves in a fine art museum.

In class, I showed the children smaller copies of the paintings we were to study on the field trip. In particular we were going to be gazing upon Titian’s 16th-century Venus and Adonis. I pointed out the boars, a sleeping Cupid by the trees, and a menacing Mars up in the clouds.

Well, my student Madeline went straight home and reported to her mother that I was showing pictures of naked women in class. Which, I suppose, was technically true. However, her retelling could, in the wrong hands, easily conjure up images of Playboy centerfolds or certain Asa Akira portraits. Thankfully, I had already informed the parents about the trip and artwork and I was not, at that time, working for a reprimand-happy administrator always on the lookout for misunderstandings to use as an excuse for write-ups. The mother laughed as she recounted her child snitching on me.

I, on the other hand, now knew who would be the first student to rat me out as a subversive during the next dawn of fascism. I was like, “Okay, Madeline. I got your number, girl.”

Elementary school can feel like a constant game of balancing potential episodes of shaming against creating space for wider inclusivity and diversity. There are tightropes being walked by well-meaning teachers trying to be vigilant of what might offend or upset parents and children while at the same time accidently doling out copious amounts of embarrassment.

Shame, misery, misunderstandings are nearly impossible to avoid in our profession regardless of all our anticipatory precautions. An educator learns how to be better simply by accruing of trove of experiences of red-faced humiliation and tear-soaked sorrow.

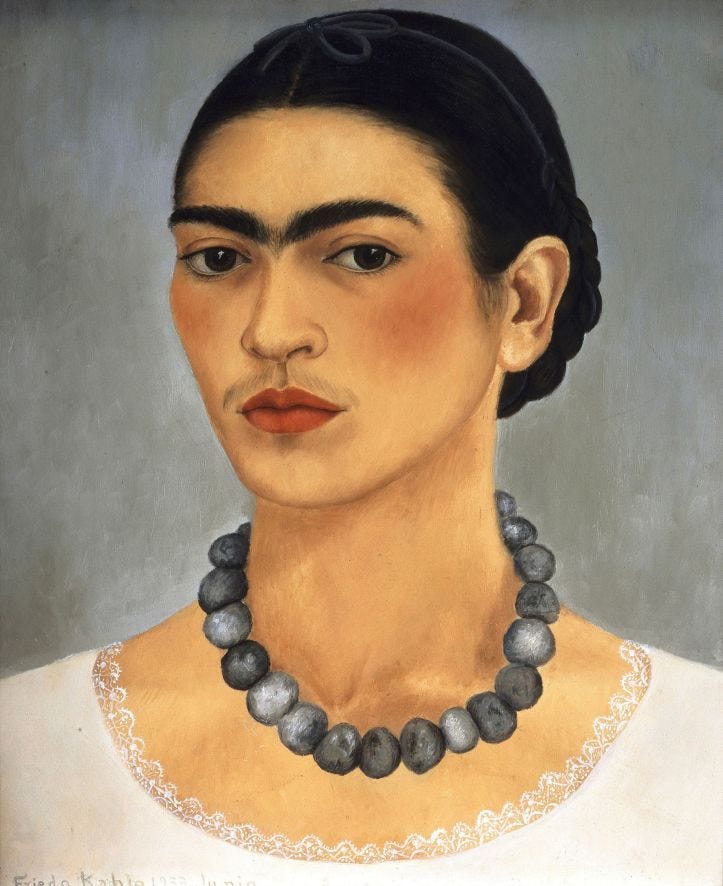

Portrait of a Lady

I had the sweetest Guatemalan girl enrolled in one of my kindergarten classes. She was always very put together, constantly outfitted with her hair done up like a celebration. Sharp as whip, she arrived to kindergarten mid-year, which is a challenge for any student of any age but particularly for an immigrant little girl like herself. However, Maria turned out to be one of my brightest students despite only speaking Spanish and not knowing anyone. Her monolingualism wasn’t much of a problem in my class because many teachers and schoolchildren also spoke Spanish, but sometimes I would forget to translate instructions for her because she was so capable and competent with picking up context clues. She was a fast learner who often took initiative and tried really hard at understanding what was going on.

On one particular day the class was working on self-portraits. I was offering step-by-step instructions on how to draw the features of their faces using my own face as the model on the board. My own picture included my big mustache, two black, droopy eyes, a long face, bushy eyebrows, and short black hair. The children were supposed to follow my instructions but draw their own faces and features while sitting at their desks.

When I walked around looking at everyone’s progress, I noticed Maria had mistakenly drawn my face—mustache, goatee, and all—onto her paper. I had forgotten to translate for her and specify for her to draw her own face not copy mine! She had just gone along and copied what I was doing because she was such a good follower of instructions. I spontaneously laughed out loud because it was so funny to see my Latino man-face amongst all these kids’ faces drawn in crayon and pencil. And hers was so good! The drawing looked just like me. She was a true portraitist.

But Maria burst into tears.

Oh my. I immediately apologized and told her I forgot to give her the instructions in Spanish. But I could tell she was mortified, especially because she was the type of student who prided herself on doing good work. Which she had—but of my face, not her own. I was so very sorry. I didn’t mean to laugh at her.

Had I permanently but accidentally traumatized a future artist? That was far from my intention.

Teachers can be emotional klutzes.

Educational work is hard not because we are digging ditches or mining for diamonds but because we work in these fragile, fraught environments where crying is the norm and hurt misunderstandings extremely typical.

Regardless of all the preventative emotional and language work we engage in, early childhood education is nonetheless rife with miscommunications and emotional volatility.

Unlike baseball, there will always be crying in education.