Kelly was in my sophomore kindergarten class in the 2000-2001 school year. She and her classmates were nascent millennials being taught by this here mustachioed Latino Gen X-er. There were bound to be misunderstandings.

One day, early in the year, my class was cutting-and-pasting in the copacetic quietude of an ordinary day when some errant glue accidentally smeared onto the palm of Kelly’s hand.

Jesus H. Christ!

Her screams were as startling and ear-splitting as a flash flood warning on your cell phone at three am. She was crying as if she was suddenly being stabbed by a ghost. I didn’t see anything visibly wrong with her, so I was confused.

“What’s wrong!?! Kelly, what’s wrong?” I asked as the other kids stared at us in silence.

“IT’S STIIIICKYYYY!!!!!!” she wailed.

The glue? Is she talking about the glue? I looked at her upturned hands. “Glue is sticky,” I explained.

“I don’t like stickyyyyy!!!!! My haaaands. My hands,” she sobbed as she looked down into her palms like she was auditioning for Lady Macbeth. When had cutting-and-pasting become so Shakespearean? I would’ve laughed, but I was actually concerned. And really perplexed.

What do I do? I wondered. I was still relatively new to the profession. A scraped knee, a bloody nose, even a vomiting child I knew how to handle, but how do I fix paranoid hallucinations?

Kelly sobbed in pain like her hands were on fire.

Then I thought of that scene from the 80s movie Silkwood where Meryl Streep’s character, who works in a nuclear reactor (with her lesbian roommate played by Cher), sets off a radiation detector and undergoes a violent, institutional scrub down in an emergency shower. I’ll just pull a Silkwood, I thought.

I rushed Kelly to the classroom’s sink where we washed her hands vigorously, making sure to scrub all the deadly radiation (and glue) off her hands. Then I arranged two wet paper towels on the table and had her lay her hands upon them as if we were cooling her third-degree burns with some cutting-edge triage technique. Kelly sat at table, her weeping diminishing, as she recuperated from the life-altering trauma of getting some glue on her hands.

I never figured out the root of her phobia. Her mom was clueless about it, or just kind of “Uh-huh, I know” accepting of it. With no solution at hand, I simply accommodated Kelly’s idiosyncrasy in our classroom by keeping her away from glue, tape, and stickers. She was excused from being triggered by cutting-and-pasting for the rest of the school year— like a true millennial.

The point here being: kids are fuckin’ weird.

There was no rhyme or reason to Kelly’s reaction. At least not one that she could explain to me as a five-year-old. Sometimes as a teacher you just gotta roll with the crazy. There is no time to diagnose or psychoanalyze in the moment. Your role is simply to provide comfort.

Ours Is Not to Reason Why

A therapist once advised me never to ask children why they are crying.

This confounded me as an educator. I felt like half of my time in kindergarten was spent asking kids, “Why you cryin’ ?” or “What’s wrong?” Why wouldn’t an adult ask a weeping child, why are you crying?

My therapist raised her voice in emphasis, “Because they don’t know why they are crying!” “Crying is like farting or laughing, it’s just a release of energy,” she explained. Of course, she was making a generalization, but she was also making an important point about how adults should speak to children. Don’t ask children why they are crying because they don’t know why they are crying.

Why do any of us cry? People cry for a whole myriad of reasons: because they are happy, sad, scared, joyful, disappointed, embarrassed, surprised, hungry, overwhelmed, they just won the lottery or lost a parent or heard the funniest joke of their life. Most adults themselves don’t even know the source of their own emotions. How can anyone expect a child to not only understand the multilayered emotional landscape of their interior life but then also have the words to articulate that interiority to grown-ups? Most can’t.

“Why are you crying?” is a deeply inadequate question.

If a five-year-old could elucidate, “I’m not crying because I fell down and scraped my knee and it hurts, rather I feel humiliated at falling in front of all my friends and disappointed in myself for not being careful as I ran up the stairs and scared because my mother will be upset at the sight of my ripped pants,” then there’d be no problems. But this is rarely the situation.

Burdening children with an obligation to articulate their feelings in the midst of feeling them is especially cruel for English language learners who have to translate those feelings into a foreign language.

Don’t levy such expectations on children. At least not without all the language and emotional scaffolding done beforehand.

Teaching them the language around various emotions and how to recognize feelings is a good first step before any “Why are you crying?” interrogation.

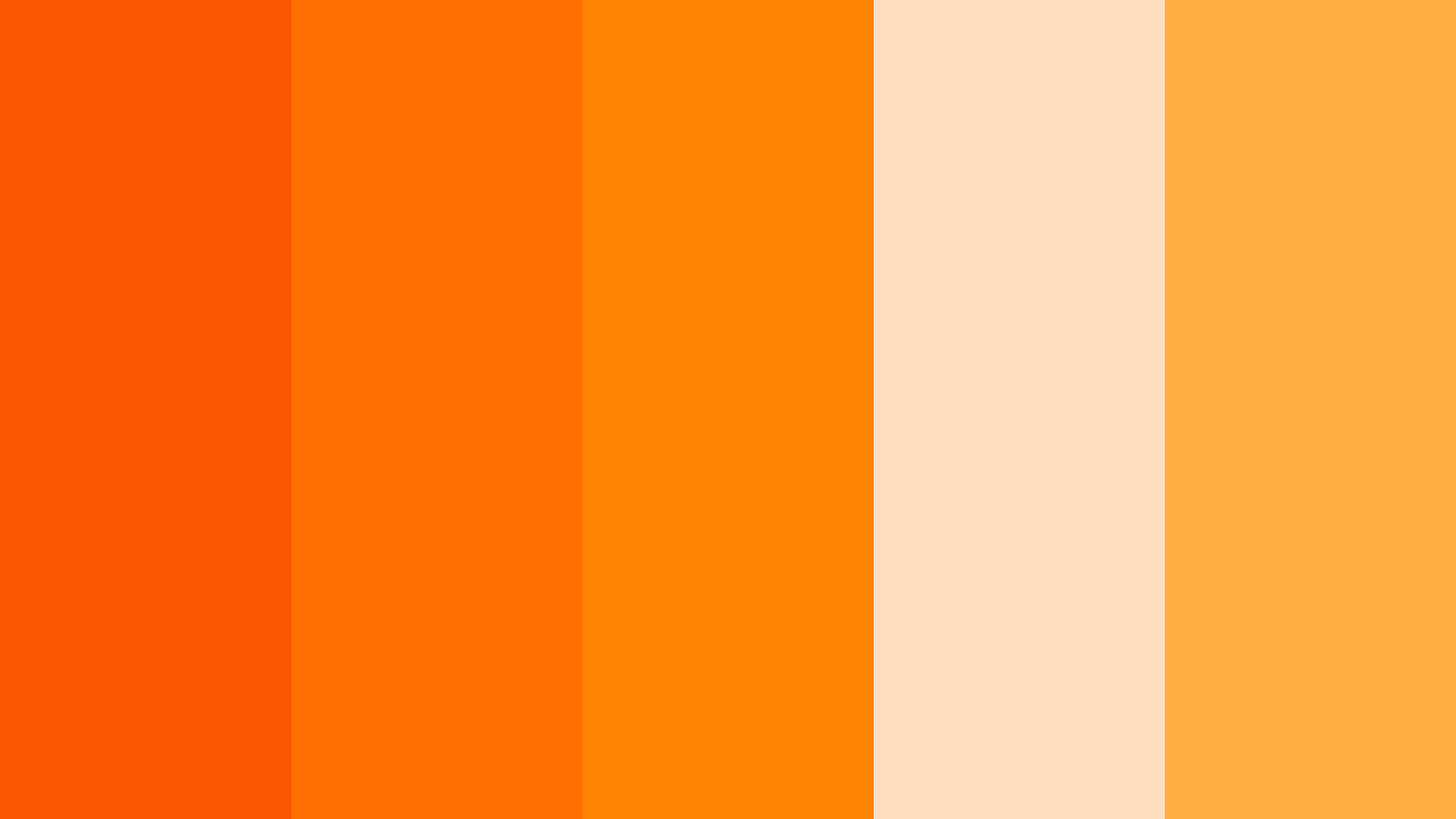

For example, having students understand how disappointment is a different shade of emotion than frustration helps tremendously with self-comfort. If the kids understand that disappointment is sadness plus hurt when an expectation has not been met while frustration is anger plus hurt when something is not working out in an expected way, they might be able to solve their own problem, or at least communicate what the exact problem is.

When children can appreciate that there is a large variety of emotions similar in range and number as the hues found in box of sixty-eight Crayola crayons, they can begin to practice conceptualizing those feelings into words and eventually answer a grown-up’s badgering questions. Being frustrated is as different from being disappointed or annoyed as orange is different from deep saffron or red-orange.

Unfortunately, more and more states are attempting to ban socio-emotional learning in the classroom because of pressure campaigns by conservatives. Such curricula has been lumped in with Critical Race Theory and LGBTQ issues in the current moral panic gripping the nation’s schools.

(Be forewarned, also, that socio-emotional education makes children more articulate and powerful. The one year I taught my preschool students the word irritating resulted in Calvin announcing one day that “Mr. Nisenbaum is irritating me!” My team partner was none too pleased.)

Damaris if you do, Damaris if you don’t

I’ve had new kindergarteners cry EVERY MORNING for TWO MONTHS straight, wailing in the classroom as if raptors are eating their livers alive. As I tried to teach, the classroom sounded like Halloween Horror Night at Universal Studios. It’s very disruptive. No amount of tender coddling can get some of these tormented students to quit their screeching waterworks. Eventually, such kids will exhaust themselves into the realization that their crying isn’t going to get them home and they ultimately surrender to becoming a student.

It just takes a looooooooong time.

I usually attempt to explain to the wailing children that their noise-making is hurting the other students’ and teachers’ ears and, therefore, I must place them as far away from the group as possible, temporarily. I realize reason is not accessible, at this point, to the children. So, I mime the pain to our ears that they are causing and empathize with their dilemma by getting down to their level and hugging them. I invite them to join us on the rug when they are ready but in the meantime, they have to be far away from the group because of the noise they are making. If there are personnel or parent volunteers available, they sit alongside them. If not, they sit alone.

When they sob to me, “I want to go home,” I tell them the truth, “I do, too.”

Little Damaris was an interminable wailer. She would cling to her mom with the strength of a little person bodybuilder. Coaxing her into the classroom while she gripped her mom’s waist was like wrenching a baby octopus from a pole. She seemed to have more limbs than an Indian goddess. After TWO MONTHS of crying every single fuckin’ day, Damaris finally stopped and decided to become one of my best students ever. Before she made that decision, however, she would sit at recess on a table afar from everyone in a misery that made her look ill. Her classmates ran joyfully around her in the play yard only accentuating her island of despair. Then one day, she just stopped her moping and joined the class. I had let her be for a very long time and I think she just finally made a better choice.

The process where students eventually make this momentous decision to stop crying and participate is opaque and internal. There is no way for teachers to access it, particularly if they don’t share the student’s language. The best tools teachers can use to handle the situation are our intuition and experience.

There really is not too much of a template for managing children possessed of this kindergarten anguish because every child is different. Coddling only seems to offer them hope they will somehow be able to manipulate you into sending them back home, call their parents, or initiate a SWAT-assisted rescue. Just tell the children the truth. You have to be here. You are not going home. And then leave them alone.

It was best that I left Damaris to herself instead of trying to smother her with coaxing and bribes and questions.

Understanding that children possess the freewill to eventually make this decision on their own can help get a teacher through the long, loud, wet process that requires at least some accommodation mixed with a high level of noise tolerance by educators.

Asking “Why you crying?” simply does not help any situation. Stop asking such a useless question.