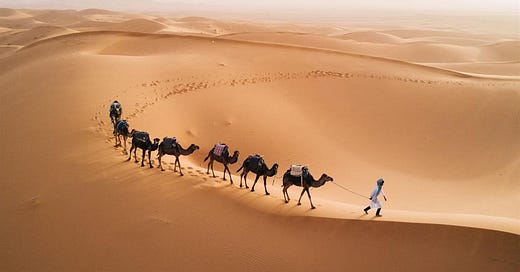

N is for Nomad

When I was in seventh grade, Mr. Jimenez was teaching us the word nomad by making the entire class repeat the definition over and over and over again.

“A nomad is a person who travels from place to place. A nomad is a person who travels from place to place,” we chanted as if we were praying a rosary decade. Immediately after the umpteenth time, Mr. Jimenez suddenly turned to one student and asked, “Alfonso! What’s a nomad?!?”

Poor little Alfonso. He was so flabbergasted at being selected that he froze like a frightened baby goat. Despite the fact we all just a nanosecond before had been repeating the answer out loud, Alfonso didn’t know what a nomad was. He had been lulled into a daydream by our nam-myoho-renge-kyo chanting.

All of us seventh graders looked at him, thinking, what the hell? We were all just repeating the answer! We stared at Alfonso, trying to telepathically transmit the answer to him with our wide eyes, “A NOMAD IS A PERSON WHO TRAVELS FROM PLACE TO PLACE!!!!”

Whispers of “Alfonso! Come on!” erupted as our classmates grew uncomfortable with the tension in the room. Soon enough little Alfonso cracked. He looked down into his lap. Defeated. About to cry. He had no idea what a nomad was.

Mr. Jimenez was, of course, incredulous.

He called Alfonso up to the doorway, and they left the classroom together. He escorted him across the play yard into the parish church as the class waited, curious about what was going to happen. Mr. Jimenez returned to class without Alfonso and without revealing what he done to him. Did he murder him? Send him home? What the hell happened? Mr. Jimenez continued the lesson without ever telling us.

My sixth grade teacher Ms. Cabonbon did something similar to me. We were practicing our multiplication tables when she suddenly and unexpectedly called on me, asking what was 8 x 6. Her questioning felt like a jump-scare in a horror movie. In that very instant all multiplication was wiped from my brain. I went blank. I didn’t even know what numbers were. With everyone looking at me I melted into embarrassed tears. I was so traumatized that even now in mid-life I can barely multiply by eights.

My seventh grade class later found out that Mr. Jimenez made Alfonso walk from votive stand to votive stand all around the inside perimeter of the church, blowing out and then relighting each prayer candle in an attempt at re-enacting a person traveling from place to place. He wanted to make sure Alfonso knew what a nomad was.

Now, I don’t want to be Judgey McJudgerson on Mr. Jimenez for his teaching tactics, mainly because I have executed similarly inefficient vocabulary lessons (and odd punishments) in my career. But it should be obvious that strategies such as choral repeating of vocabulary words are very, very ineffective. In Mr. Jimenez’s defense such tactics do buy educators instructional time to cover topics we consider more vital while getting small, insignificant lessons out of the way.

There’s an assumption, often by those outside of education, that learning is an even and efficient process. A teacher presents material, razzle dazzles the crowd with an activity, and subsequently the skill or knowledge is, abracadabra, magically and permanently transferred into all the students’ heads and hearts. Tell them 2 plus 2 equals 4 and, tada!, everyone now understands that 2 plus 2 equals 4.

Teaching is not like this. It never has been and never will be. Repeated, differentiated, and creative practice will always be required.

Regardless of knowing this, I don’t imagine any diminishment in teachers’ use of, say, writing spelling words ten times each or even a cessation of our long-winded lectures.

The best of teachers falls into the trap of standing up in front of a class and inundating the children with a waterfall of words, words, and more words. We are the true Chatty Cathies of our classrooms, not our students.

But truly, our words don’t teach.

The paradox in the idea that words don’t teach is that a teacher’s daily life is built on words. It’s a verbose and loquacious occupation. We are talking, lecturing, bellowing, explaining, reprimanding, singing, signaling, facilitating restorative justice circles, asking questions, chiming, rhyming, explaining, castigating, eliciting responses, repeating, interrogating, and announcing all the live long day.

Teaching is talking. But when we are talking not much is really sticking.

Destiny, who I taught for two consecutive years in both preschool and kindergarten, couldn’t name the months of the year or days of the week for the life of her.

It was as if February and Tuesday were mysterious, alien words she had never heard before. This was despite the fact that I had gone over the calendar EVERY. SINGLE. MORNING. for two years straight. This little girl remembered the entire plot of The Good Dog by Todd Kessler. She drew the Delta airlines name and logo from the memory of her last trip to El Salvador. She could identify every classmate’s backpack along with their jackets. But ask her what month it was and she was stumped despite the fact that I performed my calendar vaudeville act in front of her, essentially for her, every single day for years (complete with Greg and Steve song-and-dance numbers).

This, of course, is maddening. Infuriating, even. I understand the fury Mr. Jimenez must’ve felt when Alfonso didn’t know what a nomad was.

I once had to apologize to a couple of fifth graders because I screamed at them for not being able to name any of the seven continents. In my mind there was no way they had not come across that information in the past six years of their educational careers.

I was pleading for them to name of just one single continent. I would’ve accepted America as an answer, even Pangea. But they couldn’t or wouldn’t. They sheepishly answered Los Angeles or Mexico probably just to shut me up. But it didn’t work. “A continent!” I shouted like some crazed game show host. But they didn’t know. They probably never knew. And worse, they didn’t care. Continents, countries, counties, cities— they were all the same to them. I might as well have been asking them to name the seven chakras or dwarves or deadly sins. It was all trivia to them. All I got offered back were blank, bored stare of disinterest. Emptiness.

Because words don’t teach.

I understand how counter-intuitive it is to say that words don’t teach because teachers use words to teach all damn day long. But I think we also must admit, if we stand back and reflect, that educators go to work every day and sound like Charles Shultz’s Peanut cartoons where all the grown-ups speak in the same incomprehensible (to the audience) sad trombone sound, “Wah wah wa wa wa wah.”

N Is for Nonsense

If you are a teacher you have to come to terms with that fact that MOST of what we are saying is being received as nonsense.

But because students are powerless, they typically go along with whatever theater of the absurd the educator is engaged in. I remember trying to introduce Rudolph the Rednosed Reindeer by singing it to a 4-year-old little vato with a shaved head and a bad attitude. He looked at me like I was a nutcase.

A first grade colleague was administering a language assessment, and one of the questions required the student draw a line from a circle and the picture of a bee. The test was measuring the student’s receptive English language, determining whether the student could understand and follow directions in English.

What should have taken the student a second or two of simply drawing a line between two objects ended up taking much, much longer as the student carefully drew an intricate figure between the circle and the bee. My colleague waited patiently, not wanting to interrupt the student, curious as to what he was drawing so intently.

It wasn’t until a minute or two passed that she saw the feline features and realized the student had drawn a LION not a LINE between the two objects. He had misheard her say, “Draw a lion between the circle and the bee.”

I mean, was he wrong?

Either way, both interpretations of the instructions are sort of ridiculous, right? There is no rhyme or reason to draw a line (or a lion) between a circle and bee. But children learn that to do well in school they just have to comply with whatever the teachers ask—draw a line, draw a lion, fill in a bubble, circle this or that, stand up, sit down, get back, turn around, stop talking.

Schooling becomes a more consequential game of Simon Says. Just do what you are told, and no one will get hurt. The best students do this with aplomb. And the best of the best often become teachers themselves, repeating the vicious cycle.

This is the aspect of schooling that cultural critic Neil Postman has critiqued. He noted that children are not learning Math, Language Arts, Science, and Social Studies per se but rather they are learning to comply. Even when all we offer them is nonsense.

Your words don’t teach. (To be continued….)