It’s Pronounced An Eye Not A.I.

Artificial Intelligence Doesn’t Seem to be a Match for Early Education (Yet)

Language mistakes occur all the time in the early ed classroom.

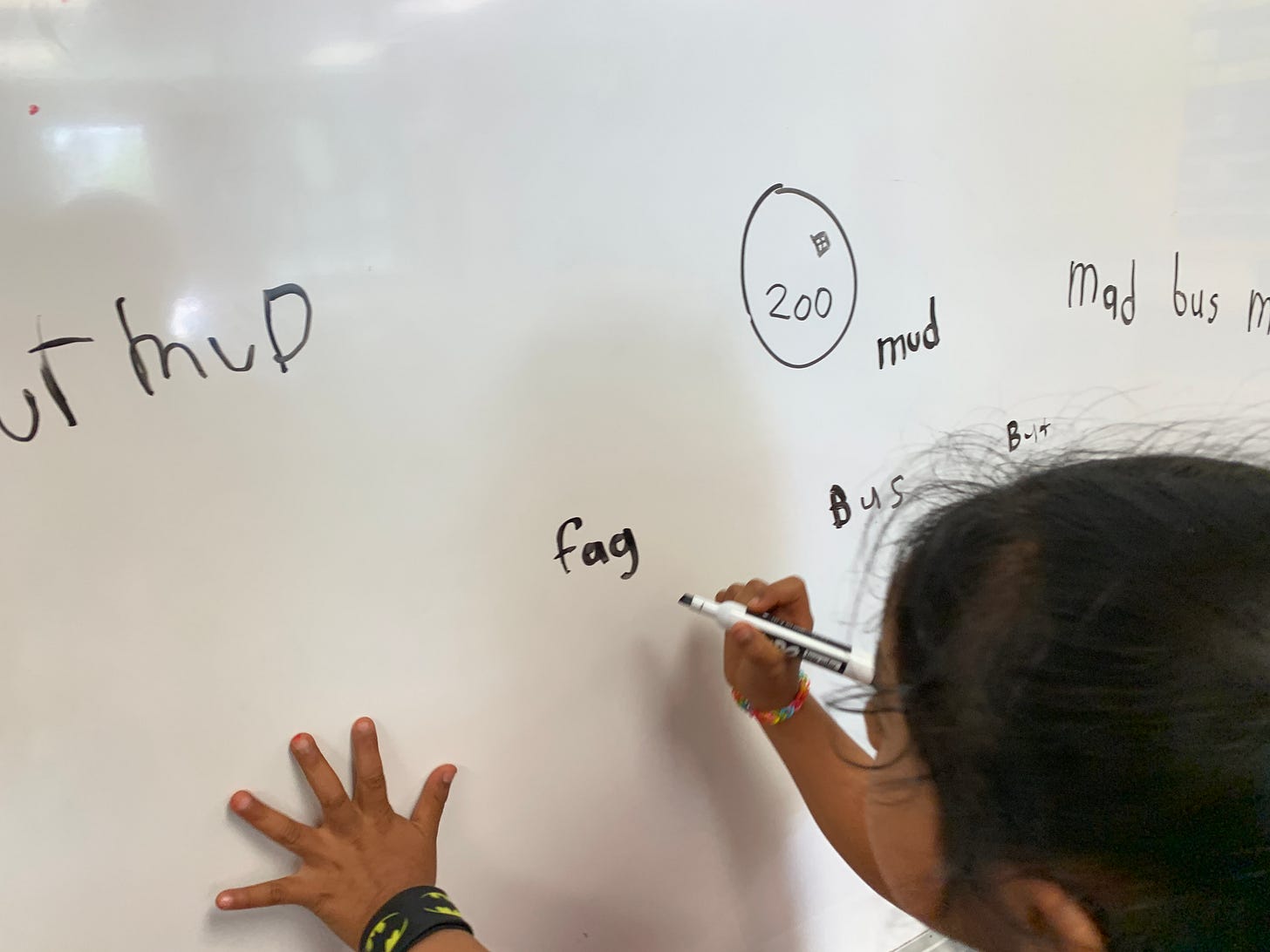

Here in this photo, I had asked Nancy to spell the word bag. She obviously heard me say something else.

Enunciate, Mr. Villegas!

Sometimes when teaching kindergarten or preschool, major language abilities would seemingly fly out of my brain. I’d be struck dumb in the middle of many a language lesson.

All at once, I wouldn’t be able to, say, name five words that begin with gr-.

Or I couldn’t readily and immediately list a group of consonant-vowel-consonant words that contain the short o sound (cot, rot, mop, log, bot).

With forty-plus eyes staring up at me, a language lesson would all of a sudden feel like that Billy on the Street episode where Billy Eichner runs up to a woman and demands, “Name a woman! Name a woman!” and for the life of her the flustered woman can’t name any woman- not even herself.

Maybe, as a harried, overworked professional, I’ve had too many things on my mind or haven’t prepared enough for the lesson at hand, but for some reason, sometimes, even the simplest language tasks would be daunting for this UCLA/USC grad.

Teachers are often multitasking their actions as well as their thoughts in real time giving our overloaded brains whiplash. Too many things are being thunk at once.

For example, trying to discipline the class, keep track of the time, hold my bladder, supress my growling stomach, and not to blurt out the wrong four-letter word as we rhyme the words luck, duck, muck, buck, cluck can prove to be stressful.

Neural connections can too easily get crossed.

This multitasking is what makes curriculums and reading programs so useful. They come loaded with already made lists of words that help you teach the students how to blend, spell, rhyme, chant, syllabicate, and more. Sometimes an educator doesn’t even need to think, all they have to do is read the provided script (I don’t endorse such teaching!)

Now A.I. has come along and seemingly placed all this knowledge at our fingertips and is scaring some teachers into thinking that they maybe, might, at some point, be easily replaced as delivers of these curriculums.

But I’ve noticed a problem.

The A.I.’s are often wrong. Even about the easy-peasy-lemony-squeezy stuff.

Over the past few months, the AI systems I have tried, both Goodge’s Bard and OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3 (I’m not on ChatGPT 4 which is supposedly much better but costs a fee) have been spitting out consistently wrong answers for me.

Especially for something as basic and simple as syllabication.

Bard and ChatGPT cannot syllabicate correctly! I have asked them to do so repeatedly.

Below, Bard incorrectly lists ambulance as having one syllable, motorcycle as having two, and, way at the bottom, doctor as having three.

In this example, ChatGPT lists elephant as having two syllables, caterpillar as having three, and giraffe as having three, also.

Why is this task so difficult for these intelligences?

Granted, here I am complaining they can’t get something right that I find difficult (or at least too time consuming): thinking up lists of words to syllabicate in the moment.

When I have tried to come up with words to syllabicate on the fly in the past I have to take weird pauses to even think of such simple words as window or January. It turns out syllabication is a very thoughtful process. Too thoughtful.

That’s why one of the first things I asked A.I. to do for me was generate these lists. It would save me loads of time and thinking energy.

But as of right now I still have to edit the A.I.’s work. Maybe these artificial intelligences will be able to do this simple task correctly in the future but as of right now they are not successful.

What is hard for me to make sense of is the fact that these Large Language Models that these apps are based on have apparently read all of Shakespeare but somehow don’t know that am-bu-lance has three syllables not one.

I think this seeming paradox demonstrates how these machines are not actually doing language in the way human beings do language.

While they can spit out “original” poems about shoes in iambic pentameter (which, by definition, needs to count out syllables) they don’t “know” that the word alligator has four syllables not three. How is that possible?

I assume it’s because they don’t “know” anything, they have simply scanned everything.

The A.I.’s can define what syllables are because they have scanned all the dictionaries are but they don’t “know” what syllables are because they have never “heard” a syllable. At least not in the way that human kindergarteners or human preschoolers hear syllables.

The machines are not doing language. They are computing language. They are scanning language. They are predicting patterns of language.

They are definitely not doing language the way a preschool teacher does language.

We mess up language both purposefully and accidentally. Our teaching is a mix of intention, inattention, and attention.

We play with it, we sing it, we ask Nancy to spell bag and she hears something else and we laugh and take picture because it’s perversely funny for this cute, lovable five-year-old to write out such a hateful slur.

Our mistakes make us more human. Our mistakes makes us more of what we are.

A.I.’s mistakes make it more what? A.I.s mistakes don’t make it more A.I.

Scared of A.I. ? Become a preschool teacher.