I’ve never understood The Reading Wars, that ongoing series of policy debates and political battles over how exactly to teach children to read.

I happened to enter into teaching right at the moment my school district chose a side. They adopted a systematic phonics-based reading curriculum a year after I became an educator. Phonics-based instruction won. At least, locally.

There was no debate or options for a new teacher. Educators weren’t given free reign to use a “whole language” or “balanced literacy” approach. As a new employee I was going to teach phonics in a daily, systematic, and explicit manner as a term of my employment, and my district was going to show me exactly how. We were hooked on phonics from the get go.

Back at the turn of the No Child Left Behind millennium, California school districts were flush with money for teacher training. I remember a reading curriculum workshop being held at a downtown L.A. hotel which provided teachers a hot lunch served on actual chinaware inside an actual ballroom. We were even provided silverware like we were billionaires at Davos. We had many, many of these trainings with such accommodations. Nowadays, a bottled water and a restroom seem to be the most luxurious accommodations offered at teacher trainings.

Looking back, I’m grateful for my district’s decision to choose phonics as well as offer a massive amount of training because, here’s a confession, I don’t think I really knew phonics before I became a teacher.

Subconsciously and intuitively, I obviously understood phonics otherwise I wouldn’t be able to read English.

I mean to say that I didn’t have the meta-awareness of the puzzle that is the English language nor did I have the skill to explain how that puzzlement worked in order to give a bunch of five-year-olds literacy.

Knowing how to read cat vs. Cate vs. Kate vs. cite vs. kite vs. night is not the same as understanding why there is a difference between them and explaining how that difference works to children.

The phonics-heavy reading program I was required to use as a teacher ended up delivering results. Not always and not one hundred percent across all children, but most students, English language learning students especially, learned how to read. And I learned how to teach human beings how to read.

Today I privately tutor children in phonics at a hefty hourly rate.

The irony for me in this situation is that something that I provided for free (at least, free to the students of California public schools) didn’t always seem to be valued by those receiving it. Now, a whole other segment of the population pays me some cute money to teach them the exact same thing.

Most of my tutoring students today come from non-English speaking homes and have the means for private tutoring as well as for stylish Gucci children’s wear. They are building up their language skills (with my help) in order to compete with native English-speaking students who are vying for coveted spots at elite preschools and kindergartens in the local area.

Phonics is for millionaires. It’s that valuable.

Sometimes it feels like in capitalism there are these open secrets and, if you follow the rich people, you can kind of figure out what is actually of value in society.

I don’t mean understanding which brand of purses to purchase or which cars to drive or hotels to stay at when in St. Croix. I mean knowing what to actually invest your precious money and time in order to receive both material and psychic benefits in return. Yeah, stocks and real estate and blah blah blah, but also phonics.

Phonics is a great investment. And wealthy people know it. Why some districts and teachers are even taking such long time to understand this is sort of confounding.

I wish more parents, particularly Latino parents, understood the value of phonics.

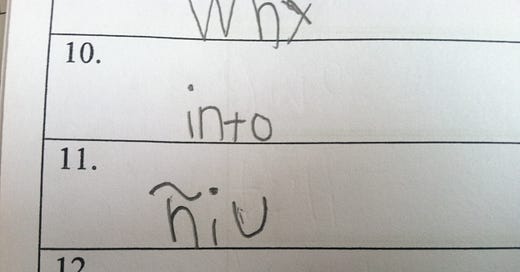

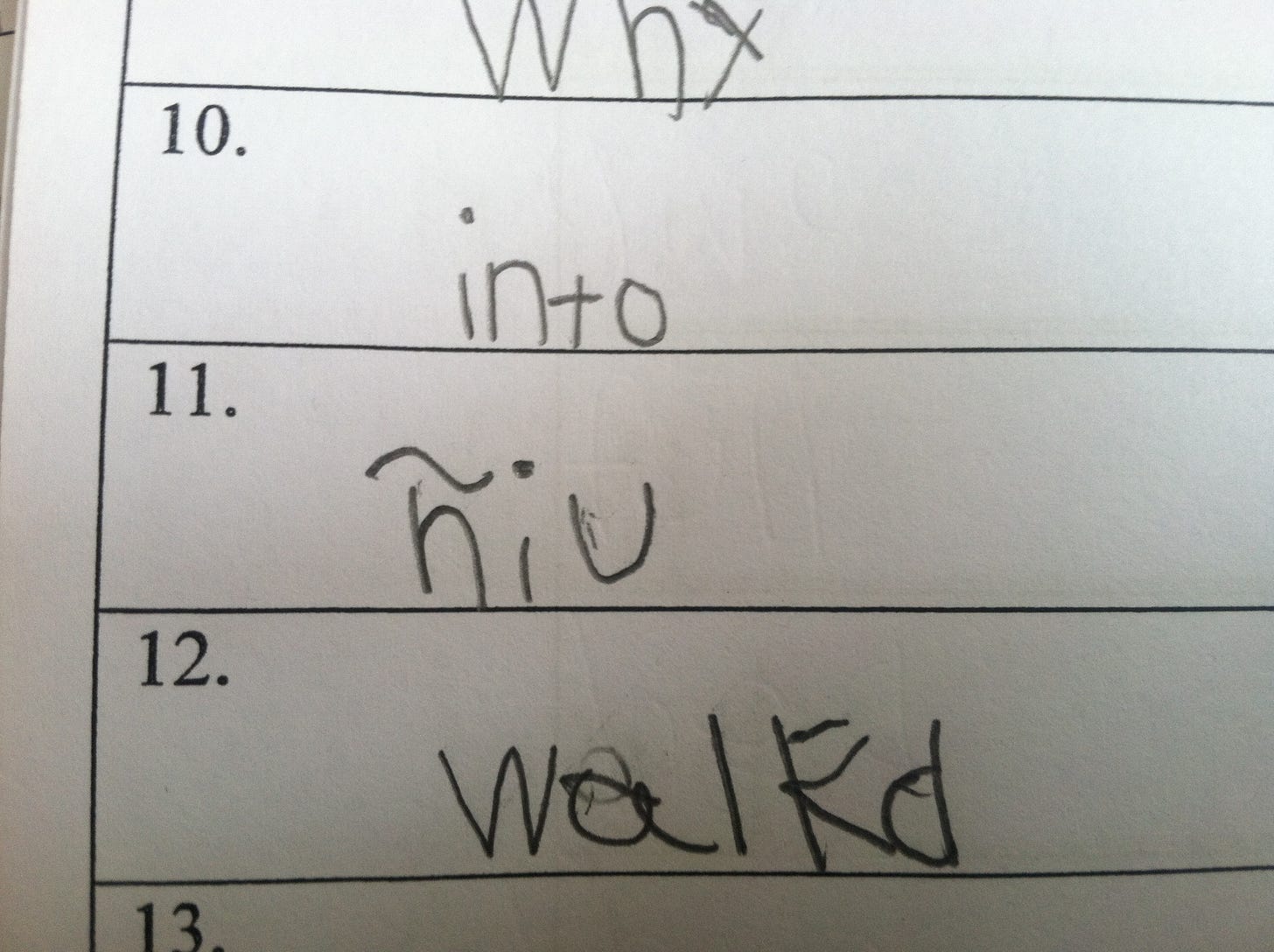

So, here are two secrets for the ñiu year.

One is that phonics is an investment. It’s an asset that will pay actual dividends in the future.

The second is that most teachers don’t actually know phonics, or even if they know phonics, they don’t necessarily know how to teach phonics.

They don’t know how to deliver phonics in a systematic, daily, explicit form building upon a series of phonemic awareness and phonetic skills. This pedagogy often includes the use of rote exercises such as oral blending which is often not envogue or well liked by professional educators.

The truth is sometimes phonics instruction is boring and tedious. It just is. No amount of razzle dazzle or “rapping teachers” or fingerpainting is going to change that. But that does not mean it is not effective or extremely valuable.