I walked into my last kindergarten classroom and there were no blocks.

The class was empty and clean. Too empty, too clean. As I stood there surveying the sparse, unfilled room, something about the extreme barrenness of the classroom struck me as odd. I soon realized, there were no damn blocks. There were no wooden unit blocks! Not even the second-rate colorful foam blocks were present. The blocks had been removed from the classroom.

I clutched my strand of teacher pearls in absolute horror.

If you ever walk into a kindergarten classroom (as a teacher or a parent) and don’t see any blocks turn around and run the other away. It’s a warning that things are not going well.

Caroline Pratt invented unit blocks nearly 100 years ago.

The blocks were the metaphorical building blocks of her school and its play-centered pedagogy. In fact, at elite early childhood schools across the country these blocks are still an essential aspect of those high-priced classrooms.

The City and Country School, founded by Pratt, today charges up to a very modern $58,000 a year in tuition while their curriculum has maintained its traditional old-school, play-centered ideology. Parents pay a hefty fee to have their kiddos play with blocks (but it’s totally worth it).

However, in many urban school districts blocks seem optional and more than often ignored as kindergarten veers toward a more and more academic and less play-centered focus. Wealthy kids still get to move around and play, poorer kids get to sit at their desks and fill in multiple choice exams.

I took this lack of wooden blocks in my classroom as a giant red flag. A mayday, really. Play was being removed from early childhood education block by block. A foreboding welled up inside me. My return to kindergarten was not looking or feeling good from the outset.

To remedy the situation, I immediately called my former preschool team partner, Mr. C., and asked him for any extra toys and blocks he had to spare. I knew the preschool program maintained a shed filled with surplus toys that was stocked with playthings. If Santa Claus was a prepper this would be his stockpile. He opened the shed for me, and I loaded up on as many unit blocks as I could. I felt like an illegal arms dealer stocking up on grenades and rocket launchers.

That entire last year of my teaching kindergarten I secretly let the kids play as much as I could.

The teaching staff was supposed to be engaged in some weird schoolwide program of small group academic instruction with a coordinated set of group rotations, but I simply refused to adhere to that administrative agenda.

Instead, I let the children play like they do at rich schools.

Education has become ass backwards where children attending elite schools are allowed to be self-directed and engage in copious amounts of play while public schools, particularly in lower socio-economic areas, have turned their focus solely onto a developmentally-inappropriate hyper-focus on academics and reading.

Research psychologist Peter Gray has noted that the self-controlled and self-directed nature of play gives it its educative power- a power that can and has been used to foster the learning of children in the past. Yet public schools, managed by teams of technocrats, routinely marginalize play depleting the most educative and powerful tool teachers have for teaching.

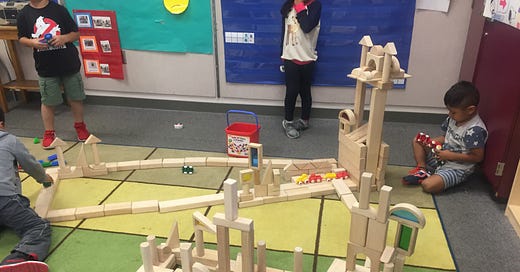

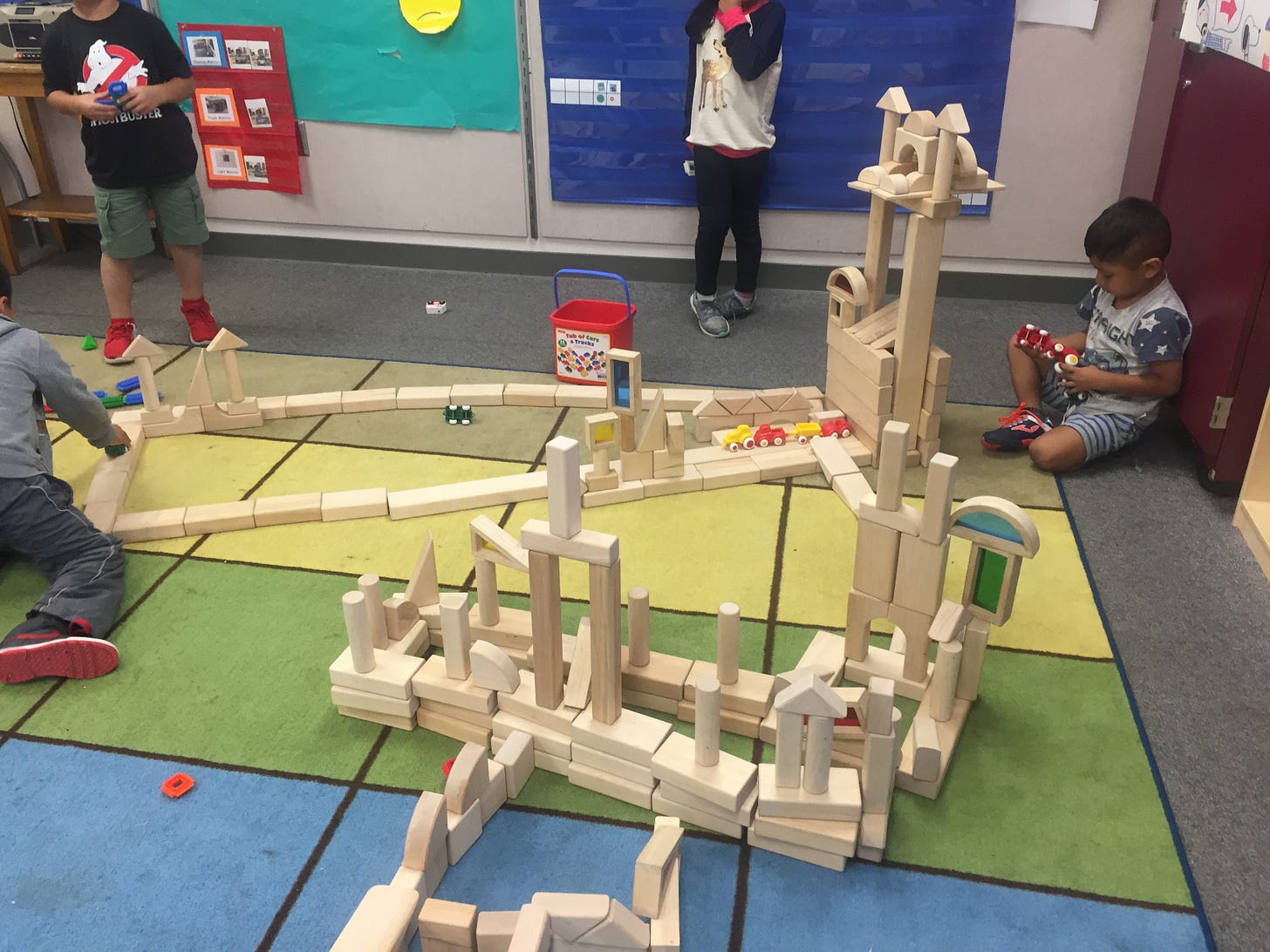

In my final year I let the kids play with unit blocks for large, unsanctioned portions of time in our daily schedule. Blocks of time were blocked out for block-play.

I often took pictures of the elaborate model cities and landscapes the children constructed with the blocks. I brought in found items and packaging leftovers from deliveries the students then used to creatively adorn their edifices.

That last year we also learned how to play a plethora of games including Kick the Can, hopscotch, Chinese jump rope, 4-corners, and Red-light, Green-Light. I brought in puzzles and Hot Wheels I bought for a dollar at Ralph’s supermarket. I let the students plunder my supply closet so they could make random crafts out of tape, markers, and colored paper at their own direction.

Basically, I let them play as if they were actual kids.

Administrators rarely came into my classroom to complete routine observations that final year. In fact, some of my colleagues grew suspicious over this obvious difference in treatment. They were getting observed with a much greater frequency than I was. But I think my superiors knew I was on my way out the door and operating on not-giving-a-fuck fumes. I was quitting and therefore a hopeless case for “improvement.”

I wasn’t playing around with my educational program.

Well, I was but I was serious about it.