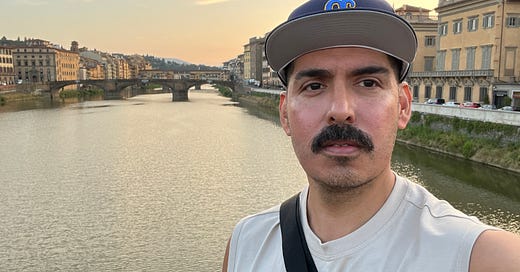

Because I’m in Tuscany on vacation this post is dedicated not only to all beautiful things Italian (Brunello wine, sexy Renaissance statues, tiramisu, the country’s landscape) but to the Italian innovators in early childhood education such as Maria Montessori (1870 – 1952) and Loris Malaguzzi (1920 – 1994) of the Reggio Emilia approach.

Late in my career I realized what I was offering my students might be too big.

It was educational trailblazer Maria Montessori who first came up with the idea of providing children child-size furniture, smaller pencils, and placing materials on low shelves for them to easily access. (Although it sounds like such accommodations would be intuitive, they weren’t!)

Utensils and furnishings of diminutive proportions give children a freedom to move about and apply themselves to creative work, Montessori insisted. Nowadays this adaptation seems like an obvious characteristic of early childhood classrooms, but it is only the norm nowadays nearly a century after Montessori first implemented the change.

The look and feel of preschools and kindergartens are not accidents; they’ve taken on a design over the course of decades that has been promoted by various pedagogues. There are entire ideologies suffused in the tiny chairs and little forks that teachers use in early ed. The tiny furniture, however, is not about being cute but about being effective and empathetic towards children.

For me, however, the problem wasn’t that the tables and crayons twere too large, it was that the ideas and lessons I was delivering were. Because most of kids I taught were either immigrants or children of immigrants I always wanted to quickly catch them up on any academic and cultural deficits they suffered. I was on a mission.

But my pedagogy was too soon overwhelmed by my political sympathies and an impassioned sense of social responsibility. I wanted to fit the world into a teacup and serve it up at playtime in order to properly prepare the students for the world ahead of them. The children simply wanted to play, and I was trying too hard to hijack their fun with some diminished form of political science 101.

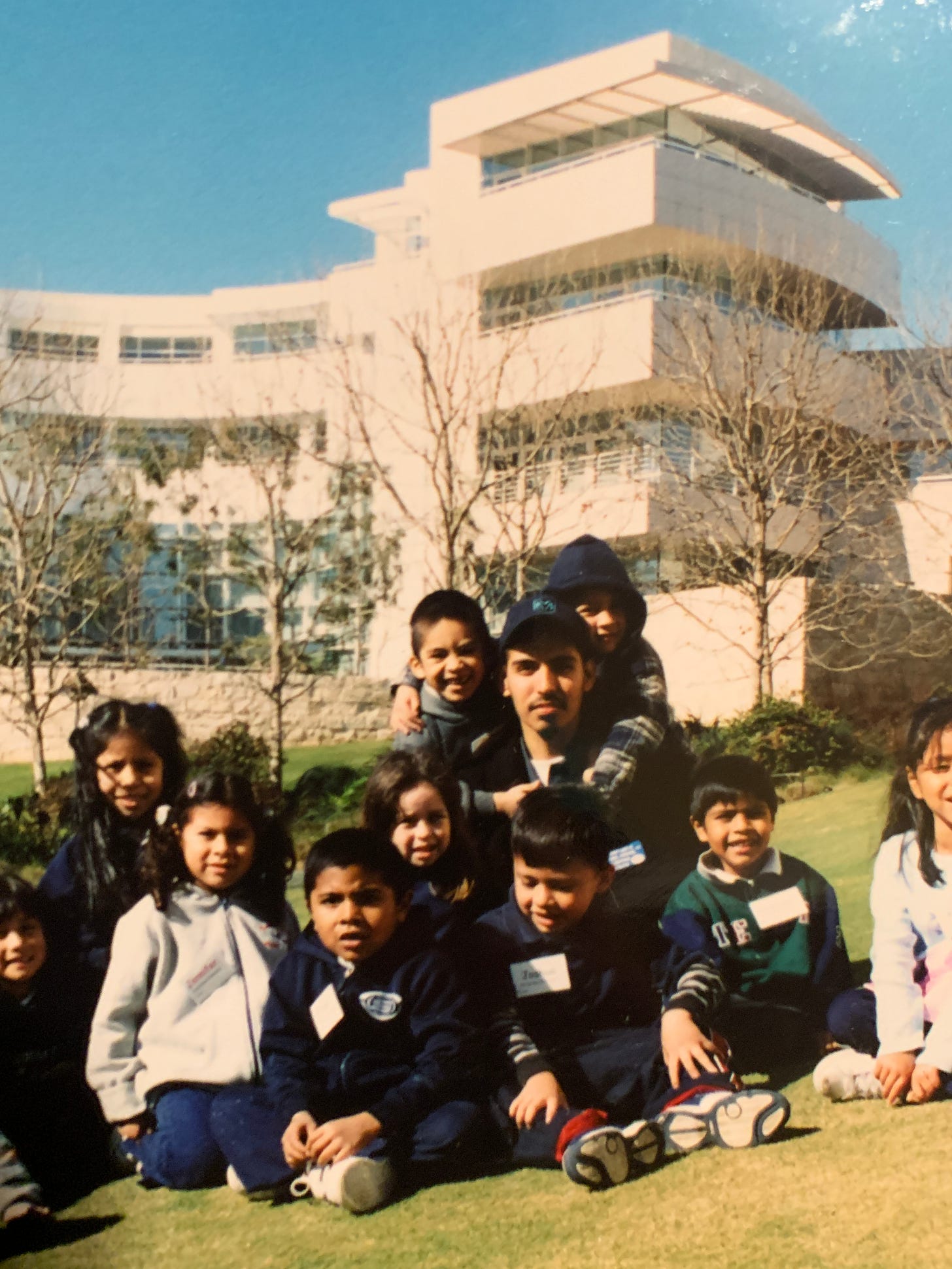

I would often drag my class to the Getty Museum, mostly to escape the confines of the classroom, but then we’d end up staring up at something as sullen as Peter Paul Rubens’ The Entombment.

We’d gawk at the gory scene, and I’d ask the five-year-olds whether they noticed a similarity between the color the artist used to paint the dying Christ’s skin and the color the painter used for the grief-stricken mother Mary. This probing question was part of our teacher-training materials: Why do you think the artist made this choice? Hmmmm. Let’s think. Maybe the painter was trying to communicate, through color, the deep sense of empathy this mother felt for her son?

The stilted script coupled with the violent imagery mostly went over their little heads.

Do you get it, Juanito? You understand, Melissa? Entiendes, Mendes? The mama was feeling her baby’s pain. Maybe Juanito and two other precocious students understood what I was saying, but all the other children were busy trying to figure out why we were taking so long wandering the maze-like galleries of this creepy church/not-church.

“When’s lunch, Mr. Villegas?” they’d ask as I tried to elicit art appreciation from little people with empty stomachs.

On our way to the Getty’s highest outside terrace, I’d speedily race them past Marino Marini’s The Angel of the Citadel, hoping the kiddos didn’t notice the statue’s generous erection. We’d then press ourselves up against the balcony's railing, touching our noses to a city’s panorama stretching from the horizontal cargo ships floating in the plain of the Pacific Ocean all the way across the arc of the sky to the vertical fingers of downtown L.A.’s skyscrapers.

It was a vast and impressive vista.

But the scene was too expansive for the kids to collapse into their minds, something akin to trying to pour the ocean into a pail.

What where these little people even seeing as we all looked out into this view of Los Angeles? I suspect they could only take in that which was close by— the railing, the shrubs below, the traffic of the 405 at the bottom of the hill, perhaps some of the Westside’s cityscape in the middle foreground, but everything beyond was nothing but a bluish blur of haze and incomprehensibility.

Did they even realize that they were peering into one of the grandest cities of the most powerful country on a planet in a solar system of eight or nine (or is it eight?) planets?

No, they didn’t. They couldn’t.

“Mr. Villegas, I’m hungry,” they’d repeat.

We would then head from the terrace back down to the garden where the children found the irresistible grassy knolls. They’d race to the top of the knoll then roll their bodies down the green slopes while cackling wildly, making it seem like the entire point of the hour-long bus ride in bumper-to-bumper traffic had been to culminate in this ritual of tumbling down a hill.

This was the sole purpose of their day.

Pretty soon I figured out our field trips needed to center around places possessed of impressive moments of grass, not History with a capital H or the Renaissance art of the Antwerp school or didactic stone monuments and plaques or even fantastic cityscapes. The kids needed grass.

In one of the restrooms of the Tuscan villa I am staying at (yes, I realize how obnoxious that sounds) there is a painting where the distance is rendered in blue.

Rebecca Solnit in The Blue of Distance has a gorgeously rendered essay on the use and meaning of the color blue. She describes how the world is blue at its edges and at its depths. She also mentions how in the 15th century European painters started rendering what was far away as blue. She connects the color blue to distance and to loss. Then she notes how as we get older that which is faraway (the past) becomes more vivid while the nearby (the present) becomes vague.

In the essay she moves beautifully and instructively into describing children’s sense of what is important,

“For children, it’s the distance that holds little interest. Gary Paul Nabhan writes about taking his children to the Grand Canyon, where he realized ‘how much time adults spend scanning the landscape for picturesque panoramas and scenic overlooks. While the kids were on their hands and knees, engaged with what was immediately before them, we adults travel by abstraction.’…There is no distance in childhood: for the baby a mother in the other room is gone forever, for a child the time until a birthday is endless. Whatever is absent is impossible, irretrievable, unreachable. Their mental landscape is like that of a medieval painting: a foreground full of vivid things and then a wall.”

Solnit and Nabhan articulate a tension I always experienced as a teacher of young children, but I couldn’t put my finger on: teachers try to reveal the distance, the bigger picture, the abstractions of life, to their students while the students, instead, are entranced by the near, the immediate, the closeby.

On a field trip to the zoo, our group sauntered into an aviary with cages containing magnificent raptors. Kevin, however, walked in and immediately pointed at the cobwebs in the corners between the cages. His eyes were wide as his mouth formed an astounded “o.” He was in utter shock…at the cobwebs. “Look!” he said to his friends.

I was dumbfounded, too. Really, Kevin? There’s a bird nearly as tall as you with a beak like a shiv sitting in a cage and you’re amazed by the cobwebs?

A colleague told me a similar story about when her son was a toddler and they visited the Tokyo Zoo. He was more engaged by the pigeons pecking the ground around them than by the exotic and charismatic animals in the exhibits. Pandas schmandas, just look at the pigeons!

It turns out the best teaching of young children is close by, it’s near, it’s concrete, intimate and immediate, at our feet and fingertips, on the floor, here, right here, now.

I’m telling teachers and parents that it’s a waste of time and money to try to ta-da! the grandeur of the background world to young kids when there are cracks in the concrete to contemplate and free lint in their pockets to manipulate.

Who cares about literature or environmental racism or peace on earth when there is an empty cardboard box right in front of you?

It turns out my favorite teaching moments were always simple and mundane: my co-teacher Mr. Nisenbaum demonstrating to a rapt audience of four-year-olds how to pop popcorn, Ms. Leslie Lewis warbling Gershwin standards to her kindergarteners, my students and I blowing bubbles made of Dawn soap and corn syrup and being flabbergasted at the largest of the orbs, us hunting for ladybugs in the native garden and finding yellow ones instead of red ones, us learning to draw a cube, fold a paper airplane, cartwheel, whistle, snap our fingers, grow a bean in a cup, rhyme, clap to a beat, play Kick the Can, write our names over and over again until they are assumed into the movements of our fingers, made to be as much a part of our being as our gait, the way we dance, and the way we hold ourselves when photographed.

Only with a maturity do we eventually need the bigger picture, the vistas and views, the context, the landscape, the history of history. Preschoolers and kindergarteners study the details of the world not knowing they are the details.

The bigger picture encompasses too much noise. That’s all for later, context comes later; the bigger story is for a more mature moment. Unless they ask why, spare children the news of that unending tragicomedy of assassinations and sex scandals and corruption and abnormal weather that adults seem to be entranced by on their various screens and in their grown-up conversations. There is more than plenty of time for that down the road.

The day after the 2016 election, my preschool class went on a pre-scheduled field trip to the L.A. Zoo. That early morning, as we prepared for the arrival of the bus, many of the adults looked demoralized. The mothers, some of them undocumented immigrants, asked what I was feeling. They admitted to being frightened. I pushed away any sadness and anger and insisted we all focus on our day with the kids. There were animals to see. I was already too exhausted by grief from the night before to have any more conversations about politics and the future.

We arrived at the zoo after a short bus trip to Griffith Park. Gonzalo peed himself before he made it off the bus and into the restroom at the entrance. I re-counted everybody as we entered. Twice. We walked into the zoo in a single-file line but soon disbanded into a crowd.

We saw a sleeping lion, low-energy elephants, and an orangutan who for some reason looked wise. The emu was bored. The giant river otters put on a loud, wild, almost obscene show. By the zebra enclosure, Joseph’s little brother inserted his leg between the bars of the fence and became entrapped. His young parents blamed each other for the mishap as all three began to bicker and panic and pull at his leg until it finally slipped back out. Another Joseph, who is severely autistic, escaped his mother’s grasp a couple of times and she had to chase him down in front of everybody. Us teachers required her presence on the field trip for that exact reason. We had made a good choice. I think she was embarrassed, however, with how ill-behaved he was compared to the other children. Keeping the group together was the priority. Seeing as many exotic animals as we could was the goal.

Then the restrooms.

Then lunch.

Then re-counting everyone.

Then the bus ride back.

These were the concerns that day. Not the White House. Not the government. Not the larger world or its shambolic future.

This particular preschool class was one of the most diverse classes I ever had. The composition of peoples was impressive. I was a Brown gay man teaching children who were Ethiopian, Bangladeshi, Guatemalan, Mexican, Honduran, and Salvadorian alongside an older Jewish man who would soon retire and move to Jerusalem to join his daughter who believed all Jews were obligated to live in Israel.

We had special-ed students and undocumented mothers, working poor and middle-class families, foster kids and children awarded to their grandparents by the courts. We had deeply religious aunts of an apostolic faith and parents in and out of rehab.

In the broadest sense of the word, we were Americans.

But what mattered that day was the little things, the small, the narrow, and the nearby—the zebras, our lunch, properly tied shoelaces, and, of course, staying together.

I read this while laying in bed and it was the best way to end a long stressful day. It reminded me to take time to focus on the little things every now and then. Take a break, breathe in and notice what’s in front of me.

Thank you for this moment.

Wonderful as usual x